To love these days like any other

So, I have a confession to make. I cannot read enough books about disease and death.

At first, this was a furtive and secret interest. I always felt a little bit morbid, like I was spying where I did not belong. Lest you think this is just something recent, let me tell you that several of the seminal books from my childhood were of this vein, too. Alex: The Life of a Child. Karen. One whose title I can’t remember about a girl whose sister died of leukemia. More recently: The Emperor of All Maladies. When Breath Becomes Air.

And last week, The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying, by Nina Riggs. Let’s talk about that one. Because I knew exactly what Nina Riggs meant when, after her mother died of cancer and it was clear her own cancer was quickly killing her, she explained to her book club: “For me–I can’t find books dark enough right now.” Her gorgeous, melodic, posthumous memoir is a masterpiece of the “signature commitment” of one of Riggs’ own literary heroes, the French essayist Montaigne, “to live with an awareness of death in the room.”

Riggs explains an analogy a friend shared with her:

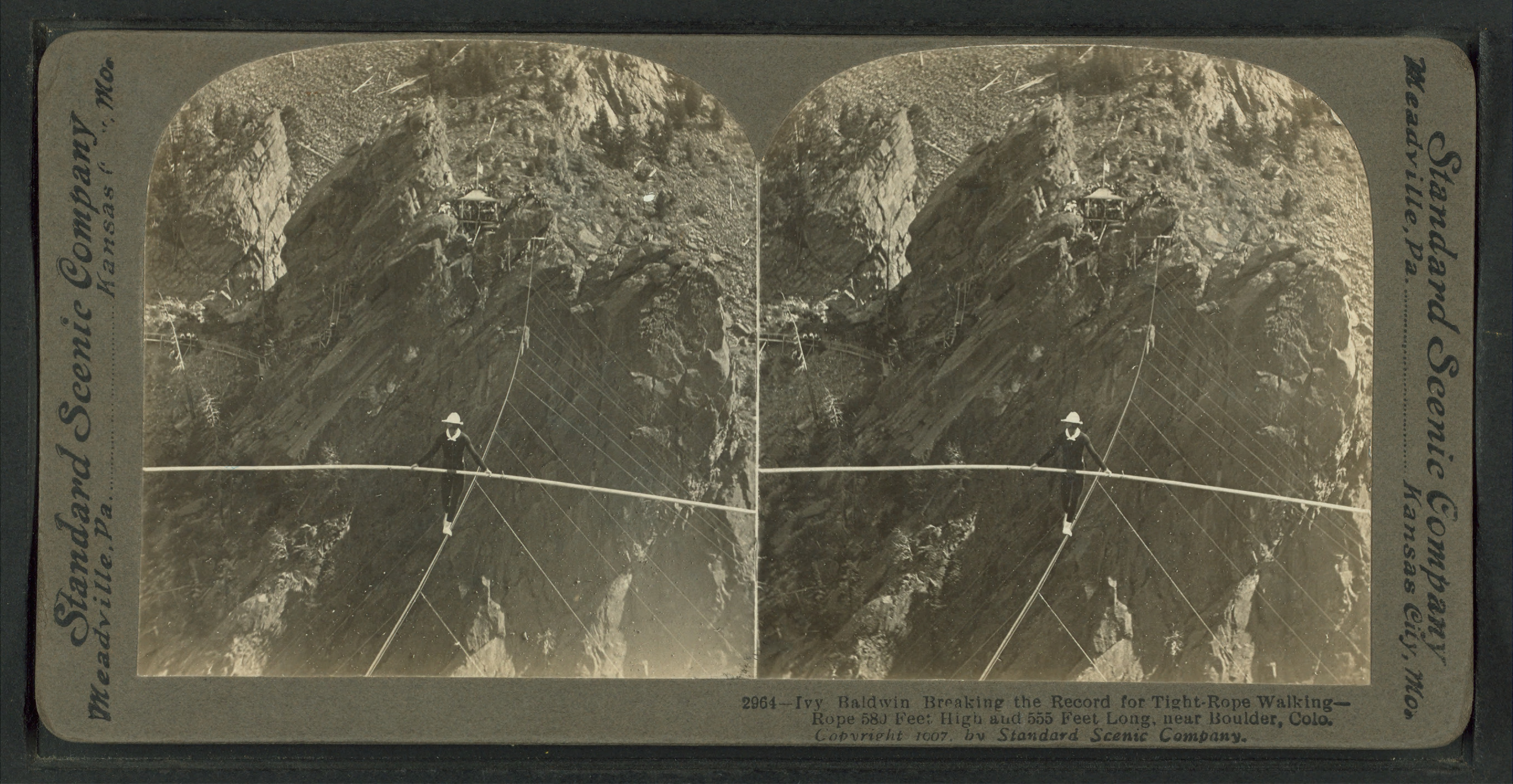

Living with a terminal disease is like walking on a tightrope over an insanely scary abyss. […] Living without disease is also like walking on a tightrope over an insanely scary abyss, only with some fog or cloud cover obscuring the depths a bit more–sometimes the wind blowing it off a little, sometimes a nice dense cover.

Myself, I might downgrade the word “terminal” to just “chronic,” or even “serious.” Moments when the cloud cover blows away and the abyss yawns up to swallow you are what you might call “Memento Mori” moments. Remember that you, too, shall die. Living with chronic disease in the house means I have a lot of them.

***

Before our last EEG in December, I was largely content to poke my head into the sand and assume that Oscar’s future was one of perfect seizure control and steady, if slow, developmental progress. The question was how far he could go, but the path to get there was smooth now. We just had to keep going.

All along, a niggling inner monologue informed me, quietly but insistently, that this was not true. I did my best to ignore it. But spending a lot of time with special needs support groups or in hospitals makes it undeniably plain: none of us are safe from the next mishap. (Nope, not even you, dearest reader.) The other shoe has dropped, now that Oscar’s seizures are back, and we find ourselves facing the possibility that we won’t regain control of them.

And because, as every doctor and therapist informs us, he can’t make much developmental progress while seizures are ongoing… this is concerning. We have already seen some evidence of this connection in the last few months. Things he used to do easily and regularly come harder, or not at all.

***

Before our last EEG, I asked Oscar’s speech therapist point blank, “So do you think he’ll ever talk?”

The elephant had been in the room at every therapy appointment for 18 months. Most of the time, we focus on the very next goal, but that day I wanted to step back and look at the whole picture.

She sighed and nodded, not a yes nod but a thinking nod, and after a pregnant pause, she was forthright. “Some kids don’t have any words until they’re four or five, and then it just clicks. But it’s concerning to me that he doesn’t seem very internally motivated to communicate.”

I nodded back. “I hope you trust me when I say I’m not holding you to any of this. I’m just trying to wrap my head around future possibilities.”

She took a moment to ask Oscar, “Do you want to eat?” She helped him press the “eat” button on his assistive device, then spooned another bite into his mouth. “I know. We both know these things can be unpredictable. But if I had to guess right now, I’d say he might end up with a handful of words, and maybe use a simple device on his own, if we can find the right input. But… He may not have much more sophisticated speech than that.”

She had told me absolutely nothing that my own heart and intuition hadn’t already said. I was grateful, so grateful to hear someone speak it aloud.

This conversation happened before we knew the seizures had returned. Before, after. Context matters.

***

I do a lot of what Todd calls “pre-processing” and what others might call “borrowing trouble.” But I am a person who lives with my heart wide open, permanently affixed to my sleeve, ready either to be poured out or to absorb the emotions around me. Or, in many cases, to be battered relentlessly. I would always prefer to be prepared for the next blow than for it to blindside me.

I do trust that God will carry us through whatever storm is around the corner. That doesn’t mean I wouldn’t also like to know the contours of the storm’s horizon before it happens. Tracking the potential cone of Hurricane Oscar.

Riggs faced a similar divide with her own husband. He was upset that she wouldn’t set aside her worries and look ahead with him to the better days that would return once she was cured. As they lay in bed, side by side but worlds apart, she tried to explain:

“I have to love these days in the same way I love any other. There might not be a ‘normal’ from here on out.”

***

De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine

Out of the depths I have cried out to you, O Lord

Psalm 130

I have spent the many months since our Lourdes pilgrimage growing lazy in the practice of my faith, fat and glowy and indolent, the cat who polished off the entire can of tuna in one go. The spiritual high allowed me to coast a very, very, very long way with little effort on my part.

But as much as I have enjoyed the months of reprieve, of peace and spiritual consolation, even of physical healing and progress for Oscar, I forgot something crucial. Those gifts were never permanent. This world is not our home. This was not about the gift of immortality. This was about the gift of being able to love the days we are living, sorrowful and joyful alike, every moment that God, in his mercy and grace, grants us on this earth. This was about learning to hold those days, those gifts, with open hands instead of clenched fists, ready to surrender them back to God at any time.

I am and always will be an abyss-starer. I pull back the hood of the specter of death to examine his face, so that I can know my enemy. I examine closely how other people face him, at horrific and plentiful funerals for people who should not, if there were any justice in the world, be dead.

But staring into the abyss without clinging tightly to the hand of God is a dangerous game. He’s calling me back to his side now. Take my hand, dear daughter. It’s time to cling again.

I want to surround myself with others who acknowledge the existence of the abyss. I steer conversations with the subtext that our lives are not wrapped up in tidy calendar-day boxes as we move in our air conditioned cars from manicured soccer field to newly remodeled kitchen. I need people who are willing to talk about what they have seen when they, too, peered into the depths.

This includes our doctors and therapists and ever-widening net of medical professionals. I want Oscar’s team to admit that yes, we are on a tightrope, that the journey is dangerous and the ending by no means certain or determined. (Well, the ultimate ending is.) I also desperately need them to do the other part of their job, where they keep encouraging us to look up and fix our eyes on the other side, or just ten yards farther along. But for me it has to be a both-and proposition or it strikes a disingenuous note.

I don’t want coddling. I want acknowledgement that walking this abyss is hard, maybe even impossible. And then I want a gentle admonition to get up and keep moving forward, for as many of these days as I have left to love.

Another beautiful post, my friend! I finally got to read it this weekend as things have been crazy. Like you, I’ve been a little lulled. After my mom passed in 2015, I had to adjust to a new normal. For a couple years now, things have seemed pretty good for my dad. However, he’s had some health problems recently, so I’m back near that abyss that reminds me I won’t always have him with me either. But hope. We must always have hope. And in the middle of that hope and that abyss, we cling to the God who loves us.

I’ll pray for your dad, and for you as you walk through whatever is next with him. The hard trick is in remembering the proper aim of hope: heaven. It’s SO easy to get sucked into the worldly kind! (For me, anyway. My hope is still pretty small and weak-kneed.)

Wonderful. Made me cry.